Windmilling his kayak paddle into the breeze, Luc Mehl, 34, pulls onto the sandbar at the mouth of Mexico’s Rio Antigua and squints at the novelty of a seascape horizon in the hazy afternoon glare. Two days of sleepless dysentery have drained Mehl’s prodigious vigor and his hands are blanched and clammy as we high-five. Still, he’s grinning with accomplishment in the salt air.

Eleven days earlier we’d set out pedaling bikes strapped with mountaineering and whitewater paddling gear in Cholula de Rivadavia, a ciudad sixty miles east of Mexico City. Without ever having visited Mexico before, Mehl composed a 220-mile bike/hike/packraft triathlon first to Pico de Orizaba (18,491 ft) and then descending through rainforest hamlets to a whitewater river. Now at sea level, we stand at the end of Mehl’s line.

Luc Mehl has risen to a sort of auspicious fame in his home state of Alaska. With a mind inclined towards calculations and an academic background in geophysics, Mehl scrutinizes topographic maps just for fun. In those maps he discovers long, elegant, and unlikely routes. With a line drawn, he turns his laser beam focus to traveling it. Completion of trips like his Mt Logan Traverse garner a mix of awe and envy from the cadre of wilderness adventurers who follow his exploits. I count myself among the admirers of his multi-sport traverses and so, without having met Luc Mehl, I’d accepted his invitation to join this trip.

Two other athletes were also enticed by Luc’s outline of a plan. Todd Tumolo, 27, and Steve Fassbinder, 38, are both veteran multi-sport adventurers. Tumolo’s work as a mountain guide on Denali and Fassbinder’s job building packrafts hint at how dedicated both are to wilderness travel. Converging for the first time in the Mexico City International Airport, Mehl, Tumolo and Fassbinder are easy to spot. Each is traveling light, wearing the only set of clothes they’ve brought. Their technical fabric pants and weathered trail running shoes stand out amid the sea of loafers and slacks.

Raised in McGrath, Alaska, population 346, Mehl abhors urban bustle. There must have been a moment when he weighed the option of a traverse beginning at the baggage claim, but settled instead for a bus ride out of Mexico City before starting. The movie playing on the bus’ little screens shows hobos leaping aboard a moving train, but I’m watching pedestrians sprint to swing themselves onto a bus weaving parallel to ours. As we burrow into the mash of nighttime traffic, I’m glad not to be on bikes yet.

We begin the hunt for bicycles the following day in Cholula. Starting at a shop that deals expensive name brands, we work our way across town searching for bargains. I imagined finding some well-built old steeds but, with none to be found at pawnshops and used bike garages, we splurge on the cheapest new mountain bikes we find. Though shiny, they’re already in questionable repair and we work into the night truing un-tensioned spokes and bolting on gear racks.

With packrafts rolled in tight burritos and strapped to our handlebars, we spin into the rising sun. The very first pothole loosens my handlebars from the clasp of the bike’s stem and they begin to spin. With plans to give the bikes away when we reach the headwaters of Rio Antigua, we’d sought cheap ones and hope our mechanical know-how will help us nurse them through the coming days of hard riding. We buy a properly sized bolt for my stem, and then replace Fassbinder’s too. One of Fassbinder’s crank arms doesn’t tighten to its bottom bracket. My rear tire blisters then explodes a few miles later. We pull over often to re-align shoddy parts and tighten bolts on our overloaded bicis.

Squeezed between semi trucks and tall curbs, I swerve over the remains of a dog. The next one isn’t more than a dry pancake but I cringe as I roll over the matted fur. The lanes narrow and the shoulder shrinks. I pedal past a third, fourth, fifth and sixth dead dog. One that’s hit but not yet dead watches us pass and the grim vision spins in my head. The frequency of road kill dogs becomes our litmus for how dangerous this road is. There’s no room for bikes in the slim lanes and we continue in the ditch, granny-gearing along sandy washes. When we turn onto a quieter route a dozen miles later, I’m relieved to find long intervals between both dead dogs and passing semi trucks.

Our route climbs gradually towards Pico de Orizaba. Its hazy triangle outline distills into a white pyramid as we crest the foothill town of Tlachichuca. The pavement ends more than 9,000 ft. below the summit but the climb continues on a rutted road blanketed by a duff of powdery volcanic dust. Sweat-slick, we’re magnets for the billows of airborne ash that swirl from our feet as we push our bikes up the steep 4wd track.

In the thin air at 14,000 ft., we lean against the cracked stonework of Pico de Orizaba’s Piedra Grande Refugio and unbuckle the ice axes that have rattled against our bike frames for the last 70 miles. From the hut, a trail leads upward through talus and worn slabs to the shrinking glacier that cups the upper slopes of Orizaba’s cone. Mehl, Tumolo and Fassbinder have fashioned insulated booties that fit over running shoes and under crampons. Their puffy Smurf feet look like caricatures, but their toes stay warm. Reaching the top at 9am, we bask for an hour and a half in the high-watt sunshine and watch black little puffs of smoke sprout like mushrooms as trash piles are lit in villages 10,000 and 15,000 ft. below.

Hours after summiting we are back on bikes, skidding around loose hairpins, and coasting through towns where the rubbish piles still smolder. Our bikes rattle one degree less since selling or gifting our ice axes to local guides. Chickens patrol these streets and flocks of kids materialize from ditches, doorways, and alleys to chase our alien gringo bike gang. The summit’s lean atmosphere transitions to a misty, fragrant one where white rivers of vapor flow up from the rain forest below. More than 12,000 ft. below our morning high point, we ask a farmer permission to camp in the rows of cornfield he’s walking. Sure, he smiles. It’s not his field.

Rather than carry food, we buy it as we move, stopping for street tacos and eating produce right from the stand. One hungry night we buy two roast chickens and savage them on the spot despite our filthy hands. People stare. We’re a conspicuous group and there’s no part of our appearance from gear-laden bicycles, to Fassbinder and Tumolo’s beards, to our roadside campsites, that helps us blend in. Every day, friendly and curious strangers wave us down to ask where we’re headed. “Vamos a la playa!” becomes our slogan.

One last switchbacking descent leads to a bridge over the Rio Antigua where we plan to put in. 60 miles and 15,000 ft. down from Orizaba’s summit, we’ve taken the bikes as far as we need them. Stripped of their loads, they creak less and feel almost nimble as we pedal into a pueblo pequeño just upstream. “Qué quiere esta bicicleta?” I ask a man delivering a sack of coffee beans. Incredulous but elated, he shakes my hand between both of his then pedals off. Our bikes twirl through town under their new owners.

The final leg of Mehl’s traverse entails paddling inflatable Alpacka Raft boats 80 miles downriver to the Gulf of Mexico. The seven-pound boats are nimble, durable, and pack down to the size of a small two-person tent. In their latest incarnation, zippers in the boats’ sterns allow us to pack equipment inside before blowing them up. With camping gear stowed, the boats have a low center of gravity that will add stability and help up punch through the grabby rapids below.

The first section of our float carries us down Barranca Grande canyon. There are few paths into the narrow jungle gorge and so the valley remains nearly uninhabited. Class III and IV rapids twist through deep shade of the 1000 foot-deep corridor and we leapfrog downstream, drifting along overhanging walls shaggy with ferns. 20 miles later, the pristine character of the river changes when the walls angle apart and tributaries carrying sewage and wastewater pour in. After each rapid, I spit river water from my compressed lips, hoping not to swallow much of it. I get involuntary sips anyway.

After our second day on the water, Mehl falls ill and spends the night retching in the bushes. The next night I take his place. Then Fassbinder. It’s impossible to pinpoint the source of our illnesses. Street meat? Unwashed produce? But the increasingly polluted river seems a probable culprit.

The Rio Antigua had grown in volume as it snaked through lush forests but as it neared the ocean, it not only became dirtier, but began shrinking too. Pumps hoovering water for pastures roar two-stroke staccato along the banks and each riffle feels shallower than the last. We know we must be close to the Gulf when the current stalls and pelicans appear.

We hit the Gulf of Mexico 14 miles north of Veracruz and find an empty, undeveloped beach. Storms have deposited a dense confetti of sandblasted tree trunks and plastic flotsam. We clear driftwood and garbage from the lee of a cactus outcrop and construct camp.

It’s sunset and Tumolo and I are catching waves in our packrafts, sometimes riding them all the way into the beach and other times getting pummeled in the break. After eleven days spent moving towards this beach, it’s gratifying to play on it.

Long trips like this one don’t always fit into a neat narrative arc. Even here at the end of Mehl’s line, it’s not a cut rope, but one unbraided. Tomorrow we’ll walk and hitchhike to Veracruz and then our group will fragment as Steve and I head home while Luc and Todd spend a few days river running. Our bikes have already spun onto their next venture. Maybe right now their gear racks are strapped with bushel bags of coffee beans as they roll a muddy jungle road. The ice axes are on their own continuum of adventures, lapping Pico de Orizaba as the volcano throws a daybreak shadow fifty miles long.

– More Photos –

Orizaba and drying corn stalks

All eyes towards Orizaba

With starry skies above, we slept under the stars for the first few nights

The bikes’ were geared for flat pavment riding and so the grind up the flanks of Orizaba was a thigh-fryer even in “granny gear”

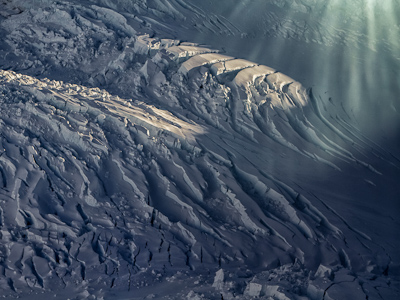

Luc scrambles towards the skeleton of the Jamapa Tounge of Orizaba’s Norte Glacier. Just a few decades ago, the ice covered a headwall that is now mostly bare.

Rocks sculpted smooth protrude through withering glacier. Scientists estimate that Orizaba’s glacier lost “72 % of its surface area between 1958 and 2007.” (J. Cortes-Ramos and H. Delgado-Granados, 2012).

Convective heating in the jungle forms afternoon cumulus clouds

Walking on firm snow before sunrise

High-speed coasting through cloud forest

By sunset, we’d descended continuousuly for more than 12,000 ft from summit to campsite.

Cheap brakepads disintegrated on steep downhills

Luc became so frustrated with hourly stops to re-tension spokes that he cut off tire knobs to allow his wobbly wheel to spin.

It’s what’s for dinner.

Doom takes a minute for oral hygene.

Overnight rust on my bike’s rims

Doom does the jungle boogie

Hundreds of acres of farmed coffee plants thrive in this forest understory.

Doom reaches the Rio Antigua put-in

Six pack for a sexy lady

Dinner time on the riverbank

Luc wore elbow pads in anticpation of gettin’ rad

Jim,

That was a most excellent write up of our trip! And the photos… Stunning.

What a great venue to forge new friendships.

Thanks Steve! Great adventuring with you! Lets do it again!

Hi there!

What a surprise… just a week ago, somebody was telling me about this people who went to Orizaba in bikes and pack rafting.

Now I found excellent pictures and report, when I was checking the pictures from Alaska.

Is nice to see Pico de Orizaba again.

Cheers from Anchorage!

It’s not a small world, just a big gang

Wow, Jim. This is what all of us adventure photographers dream of being able to not only capture, but also tell, with not just the photos, but with your elegant words, too. Bravo and please continue!

Thanks Josh! I plan to keep on keepin on. Waiting in line take off my shoes and get backscatter scanned at the airport now…

Jim,

Love the story and the photos. Excellent work and what an amazing trip! Could you give a few details on your camera/lens setup and how you kept it all running? Thanks! Looking forward to reading about more adventures.

Thanks, Shane. I carried a Canon 5d III, 16-35L, 24-70L, and 70-200 f/4, plus a half dozen batteries and cards. I keep lenses in soft cases, ’cause its easier to Tetris them in with other gear. On the river, kept spare lenses stored inside drybags that were inside the packraft tubes since I didn’t have a good system to keep them safe and dry above deck. I plan to do some customizing of my boat this summer – maybe add a behind the seat drybag like Luc’s rigged for his camera so that I can have the option to change lenses without deflating the boat.

Thanks Jim!

This was great! I always enjoy your photos and your writing is entertaining too…just enough detail mixed with human observation and subjectivity to keep it all moving along. Livens up your blog considerably.

I’m leaving for Mexico on Saturday (a family vacation, nothing as adventurous as this) and hoping I don’t suffer the dysentery/retching/dead or almost dead dog trilogy you guys endured!

Thanks for sharing!

Thanks Heather! Have a great vacation.

Jim,

Gosh I really seesaw between wishing I’d been there and glad I wasn’t — dead dog dodging on dodgy bikes while pedaling after young bucks uphill into high altitudes quick followed by bad water sounds bad — but your photos are tremendous and make my friends and their travels even more appealing. Thanks for working on the photos and the words.

Yeah, the bikes introduced some real uncertainty to the whole affair. Are you planning to paddle the GC with Forrest this fall?