I first heard of the traverse between Crestone Peak and the Needle from Austin. He had just finished climbing the Needle’s Ellingwood Arrete and was enjoying the summit when a climber asked where the traverse began. Austin pointed him towards the downclimbing that begins the route towards the Peak and was horrified when, seconds later, the soloist tumbled off the 2000′ face.

I decided to give the traverse a try in the opposite direction that the ill-fated climber took so that I’d be going up, not down, the hardest bits. We’d been working on improving sections of the Broken Hand Pass trail with the Rocky Mountain Field Institute and Mark Hesse of RMFI, wrote out a succinct page of beta with just enough info for me to find the route. An adventure was guaranteed by the broad strokes with which he described the route.

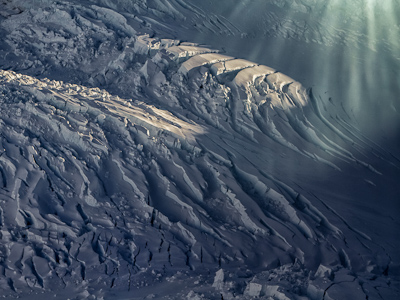

It was Friday the 13th and I left camp just as a blood-red sunrise stained the summits. Fittingly, I hustled up the the trail labeled “Friday the 13th Pass” on the OB master maps then out a narrow ridge that leads towards the north couloir of Crestone Peak. The gut of the couloir looked loose and gun-barrelish so I followed Mark’s directions and began climbing a face leading out of the gully. I moved quickly up the large cobblestone holds. Even though it was mid-August, it was below freezing in the shade of the summit and every once in a while I paused to rewarm stiff fingers. Near the top of the N couloir I crossed the loose redrock chute, and moved up a rib into the sunshine and onto the summit of Crestone Peak.

I added a “Fri the 13th” salutation to the summit register then skittered down the south-facing Red Gully before spotting a carin marking the beginning the traverse towards the Needle. Linking grassy benches interspersed with 4th class conglomerate ridges led to the base of the Black Gendarme and the crux of the route. The weakness in the NW face of the Needle consists of a steep funnel of a gully obstructed by fridge-sized chockstones. Instead of following that chimney, I soloed the 5.6 face of the couloir on steep cobblestones and thereby lessened potential for getting conked by round clasts falling from above.

A few hundred feet further up, the final pitch to the summit of Crestone Needle is 5.easy but with 2000′ of air beneath one’s sneakers. That kind of exposure is what understated climbing guides call “attention getting” and so I climbed methodically, checking carefully for loose cobbles before transferring weight to the clast. Back in the sunshine on top, the sky was cloudless and I ate a late-morning lunch and watched climbers grunt to the top of the Ellingwood Arrete. Soon, other peak-baggers began reaching the summit and as I started down I made an effort to stay out of the gully that is the most popular route to the peak. The round clasts, remnants of an Ancestral Rocky Mountains riverbed, are easy to accidentally dislodge and loose upon climbers below.

Headed down Broken Hand Pass, I was glad to be back on a trail and out of the path of falling rocks. The traverse’s exposure and big views had been exhilarating but also risky because a small mistake could have large consequences. Back at camp I began my favorite backcountry celebration sequence: untied shoes, peeled socks, rinsed off grime, and sat in the sunshine making pizza dough.