“Ha! You’ve got to be kidding me!” was Noah’s email response to a note I’d sent asking if he wanted to link up Mt Olympus with Twin Peaks. He attached a map with a red line he’d just then been drawing that connected Olympus to Twin Peaks to Lone Peak. My first thought when I saw Noah’s map was “That’s huge!” my second thought was “…well maybe.”

Yesterday morning we left the car at 4:30am and started up Mt Olympus. It was a muggy warm night with a bright moon. I didn’t need my headlamp for light; rocks and trees were illuminated in colorless moonlight. I left the headlamp on my head however. The elastic band helped redirect the sweat that was already dripping down my forehead. It was going to be a long, hot day.

We were past Mt. Olympus when the sun first glinted on the peaks nearby. The ridgeline beyond Olympus is narrow and rocky and we ducked through bushes and scrambled along the ridgeline fins. Noah called out about a ground hornet nest I’d just passed, oblivious, when he was immediately stung. A rolling talus chunk bopped me on the knob of my ankle, leaving it feeling wooden and tender the rest of the day. As we ‘shwacked down towards Storm Mountain Amphitheater we heard a startling buzz. Noah had stepped over a rattlesnake.

Mountain mahogany and gamble oak intertwine into an inflexible, woody understory and when we no longer found routes around the thickets we began plowing though. Despite temperatures that were climbing through the 80’s, I wished for a Carhartt one-piece. Even having long pants might’ve added some significant speed to our descent. Finally we reached the bottom of Big Cottonwood Canyon where we dunked our heads and soaked our feet before lacing up and beginning the next leg of the traverse.

Climbing up Stairs gulch, a trail begins at the pavement but soon disappears among scree, slab, and briers. The sun was baking the dark rock under our feet and polished slab still thousands of feet above looked wet in the glimmering heat. High-stepping up divots in slab, I understood that Stairs Gulch was literally named.

On top of the ridge, Noah’s altimeter had recorded 10,000 feet of climbing and we were slowing down. The final 1300 feet along the ridgeline to the summit of Twin Peaks took us a full hour, far slower than the pace we’d held earlier. But finally we were looking a vertical mile down into Little Cottonwood. Sandwiches and cold drinks were waiting for us at the bottom. We just had to navigate down Lisa Falls to get there.

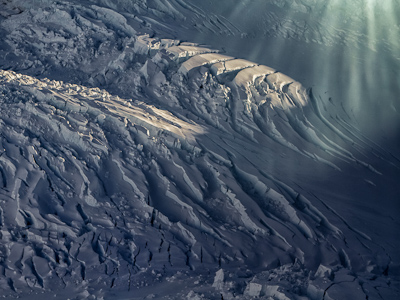

For the record, I’d like to say that I knew Lisa Falls had waterfalls – it’s right there in the name – what I didn’t realize is that over the course of it’s 5000′ run there are hundreds of waterfalls. Noah and I discovered this as we slid and handjammed down the couloir. We also discovered that, despite facing due south, there were some pretty big snow patches hidden in the recesses of the chute. The meltwater ran down the white granite, leaving the center of the gully mossy slick and limiting where we could downclimb.

We moved steadily downhill, stopping only once during the four hour descent. Earlier we’d handed hiking poles over 4th and 5th class ledges, but now we’d begun hucking poles before climbing down to retrieve them. Then repeat. Again. And again. And props to Black Diamond’s poles. Despite the abuse they’re still fully functional, though they gained a few scrapes. When my poles landed neatly paired without bouncing too far or clattering too much Noah nodded approval. Even after 14 hours on the hoof, Noah’s sense of humor is still sharp.

Finally, as alpenglow faded on the Y-couloir across the valley, we’d dropped into the deep twilight of the forest below Lisa Falls. At Noah’s truck we inhaled sandwiches and decided to save the Lone Peak to Draper section for another day. In hindsight, every part of the hike except the climb up Olympus was significantly more difficult than we had anticipated. The micro routefinding was endless and our unfamiliarity with the terrain (at least without a thick snowy blanket) hindered our ability to move quickly. If we repeated the route I’m sure we could shave off several hours. Still, the route Noah envisioned could be beyond my ability, at least if the goal is travel from Olympus to Twins to Lone Peak between sunrise and sundown. But then again… well, maybe.