Kim Havell and I have traveled together on ski trips to Bolivia and Antarctica. Working for Sweetgrass Productions, our trip to Bolivia was the first time I’d been hired to shoot a big trip rather than guide it. That was a huge shift for me and I’m sure my green-ness showed to Kim, who’s worked with the best ski photographers in the industry. By the end of the trip, we’d become both friends and fans of each other’s work. So it’s fitting that the first interview I’ve been asked to give was with Kim. Here’s the full interview:

Chris Davenport skis a chute in Antarctica. Photo by Jim Harris.

“Through The Lens” is a regular column on TetonGravity.com that highlights the work of a photographer in the ski and snowboard industries. The series exists to celebrate the photographers who bring us extraordinary imagery, to get to know who they are, and to understand their process.

Jim Harris is a TGR success story. An athlete with an artistic eye and a photographer of great strength and perseverance, Jim hit the big time from an unlikely start. Through honest and thoughtful posts on the TGR web forums, Jim unwittingly developed a huge following and grabbed the attention of industry players. Proving himself time and time again in the field and at the computer, Jim has photographs, stories, and drawings featured across varied media spots, print and online, in the world of adventure sport. He is humble, adventurous, and bright, and gets things done.

Jim has been behind the lens for Sweetgrass Productions, Powderwhore Productions, Camp 4 Collective, Eddie Bauer, Powder Magazine and more. From scaling 20,000-foot peaks in Bolivia to descending steep couloirs in Antarctica to negotiating a pack raft down Alaskan rivers, this motivated talent keeps at it as he proves that with heart and hard work, success will be a reality.Jim’s sincere and straight-up approach resonates with his audiences.

Follow his creative journeys as “The Gnarwhale” on tetongravity.com and as Perpetual Weekend online at his Blog, Facebook page, Instagram, and Twitter.

Forrest McCarthy melts water at a ridge line campsite as a storm rolls in. Photo by Jim Harris.

The Start.

I was first interested in photography when I was a kid playing with this all-metal Nikormat that my dad had brought back from Japan a decade or two before I was born. I didn’t develop a twitchy shutter button finger until I was around 16 and started documenting the graffiti scene where I grew up. Looking back at those boxes of prints, I was pretty much just mechanically recording ephemeral art.

A few years later I moved away from that scene and to Montana where I enrolled in Wildlife Biology and Fine Art courses. The blend of planning, creativity, daring, and community that made the street art scene compelling also runs through mountain culture. It only took a few weeks in Montana before I began pointing my camera at people on mountains.Studying Wildlife Biology seemed like a good route to finding a job that combined adventure with critical thinking, plus I was good at plant and animal identification.

An empirical science education has proved to be a good framework for learning about the world, even though I never took up wearing one of those flat-brim Smokey hats. The fine art courses were just for kicks, but I regret missing the memo that my university had a Photo Journalism school.

Andrew McLean skis the Chugach Mountains in Alaska. Photo by Jim Harris.

TGR.

While I’d been registered on TetonGravity.com’s message board for years, I rarely visited until I moved to the Wasatch Mountains in 2007 and discovered it offered a way to meet backcountry touring partners. Then I began posting photos of ski tours and that led to invites for more missions. One of those photo essays prompted Gordy Peifer to offer me a spot on one of his Straightline Advenutures Ski Camps, and another trip report garnered an invite to shoot with Powderewhore Productions in Alaska. That AK trip, in turn, resulted in my first print-published words and photos (Powder Magazine 40.1 “Beast out of the Earth”). Then I won a TGR and Smith Optics photo contest where the prize was an Ice Axe Expeditions ski cruise to Antarctica.

I was sharing just for the sake of sharing and that idealism struck a chord with people. If I suddenly couldn’t sell photos and stories about the sort of trips I like to take, I’d be okay going right back to doing them just for the intrinsic rewards.

Hi-fives with Andrew McLean after discovering and skiing a rad chute in the Wrangell Mountains of Alaska. Photo by Jim Harris.

Inspiration.

I admire media-makers who also are also athletes. Photographers who can climb and ski alongside top athletes are the ones who, most often I think, bring back something insightful to share.

Galen Rowell about tops my list of “photographers I wish had reincarnated as me.”Christian Pondella has crafted a career shooting photos with skis on his pack, an ice axe in one hand and that shines through in his photos.

The Camp 4 Collective team brings boots-on-the-ledge perspective to their productions and it’s apparent in the art and illustrations of Renan Ozturk, Jeremy Collins and Adam Haynes.

Leslie Anthony writes with legitimacy in his words and Fitz Cahall’s Dirtbag Diaries carry that too.

What all of them have in common is this gonzo journalism approach where, because they can hang athletically, they’re able to convey a first-person narrative that offers candid, humanizing insights into the lives of super-human athletes.

On the business side, I admire the people who help others to create content in our ski media ecosystem. When done well, enabling other peoples’ creativity is good for one’s own income. The TGR Forums empowered me and I hope the web ad revenue more than pays for the server space.

Photographers Adam Barker and Chase Jarvis both open source some of their knowledge via web interviews and tutorials. They’re investing their knowledge in aspirant photographers while legitimizing their expertise at the same time. It’s both altruistic and shrewd.

Sunrise on Illimani, Bolivia, while the city of La Paz still sleeps. Photo by Jim Harris.

The Challenge.

I want to be a really good storyteller. Sometimes when I speak, my thoughts branch into a tangent, then a tangent of that, until I’m caught in a spiraling fractal of storylines and everyone has stopped listening. So it takes some intention for me to spin a story well. Photo essays keep me on point and the narrative jogging along.

At some heady level, wilderness adventure stories like the ones I want to tell are another variant of Joe Campbell’s monomyth: the hero marches off into the wild, conquers something untamable, perhaps then realizes that the real conquest happened inside his or her head, and then returns home to share the new wisdom.

My challenge is that I don’t want to just tell those stories but want to actually watch them unfold too. Going up and down difficult mountains with interesting people carves as close to living that myth as I know how to get.

Alan Schwer hops down a steep ski line at 19,000 feet on Volcan Pomarape, Bolivia. Photo by Jim Harris.

The Business.

The business-side of working as a self-employed creative is a murky learning curve. There’s no roadmap to “making it” and even things as dry as sending photos for an editor to review turn out to involve diplomatic maneuvering. Many working photographers will tell you that your photos are only valuable if you keep ‘em squirreled away, unseen by anyone but the editor, right until they appear in print. While I see the wisdom in that approach, the only reason I’m paid to take photos now is because I’ve enjoyed sharing pictures in the past. So, I’ve continued to post photos on TGR, though I’ve become more strategic about sharing.

The ski photo world is a tough one to find recognition in, in part because much of it has fallen prey to this syndrome of collaborative competition where somebody says “Oh! Look at what they’re doing. We should be doing that too.” Photo buyers, photo makers, and athletes all push one another to converge. One outcome is that photographers face an uphill battle when it comes to creating marketable work that also conveys individual style.

On the other hand, who wants to feel like they’re walking away from a paycheck because they’re too snobby to shoot the unimaginative photo a client says they want? Faced with that question, I’m no strict idealist. I’m not exactly shooting decorative cupcakes, but I’ve dug into commercial projects, studio opportunities, and jobs outside the ski industry. Sometimes they feel like art school assignments where students replicate some Old Master’s painting. Even if it’s not an approach that I’m particularly interested in, it’s impossible not to glean something useful. Those Elinchrom-lit sets are great for learning technique but they’re not where my aspirations lie.

Tyler Jones leads a climb in the Waddington Range while Seth and Solveig Waterfall follow. Photo by Jim Harris.

Being Diverse.

When I was little I was way into these Redwall books about mice doing medieval things. My parents took me to a reading by the author, Brian Jacques, at the neighborhood bookstore and he described to us kids around him that he’d worked as a sailor, and a truck driver, and a milkman, and some jobs that I’ve forgotten before he eventually became a writer too. The notion that one could do a lot of things in a lifetime, rather than be stuck with just one profession, took root in my ten-year-old cortex that day.Photography has been my main focus for the last year or two, but it’s not my only outlet. I still dabble in woodcut printmaking, painting, shooting video, writing, and teaching. If this photo gig stops working out, I’ll always have the latitude to sidestep into one of these other roles.

Solveig Waterfall skiing from the summit of Mt Waddington, BC over a cavernous crevasse. Photo by Jim Harris.

Expedition Style.

One thing that distinguishes me from the pack is that I like unstaged, one-take, expedition shooting. Long and difficult trips are full of little victories and disappointments and they make for great photographic moments. As a member of an expedition team, I share credit and blame for the ups and downs I’m chronicling. Every bit of the process from planning, traveling, climbing, skiing, cooking, laughing and just surviving together is rewarding.

There are a couple big hurdles to being an expedition shooter. One is keeping one’s gear alive in the cold, wet, sandy, camera-killing places. That takes diligence but isn’t rocket surgery. Another is that one has to learn to suffer with grace. That takes practice and some balanced brain chemistry.

The biggest hurdle, however, is managing the dual loyalties of being both a weight-pulling team member while also caring enough about one’s audience to stop helping your buddies and grab the camera. Jabbing a camera in someone’s face in a cruxy moment can be a bridge-burning move. It takes a pretty keen awareness of the group dynamic plus articulate communication to balance photographic and team needs.

Before leaving for our first trip together, ski mountaineer Andrew McLean told me he was willing to ski for the camera but that he didn’t intend to re-hike anything for a missed shot. If you’ve skied with Andrew, you know that he zips uphill then right back down. Either I had to bully him into slowing down or learn to be quick on the draw, get the shot the first time, and not sulk when I misfired. I went with the second approach and haven’t regretted it.

One-take shooting is an ethos I’ve embraced. Shooting actual skiing down actual lines, as opposed to a choreographed one-turn-wonder approach, feels truthy. As a bonus, there’s a lot more skiing involved in a “work” day.

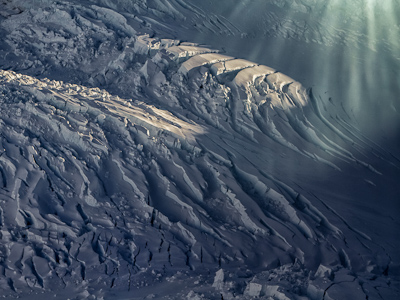

Chris Davenport skiing in Antarctica. Photo by Jim Harris.

Turning Point.

Three years ago, three friends and I spent a month backpacking and then rafting across Wrangell St Elias National Park. That trip changed my view of what’s achievable by a small, unsponsored team. I felt empowered by our success and humbled by the times I faltered.Back at home, I tried to summarize the story via a long column of captioned photos. The resulting trip report garnered a lot of attention that I never expected. Something about our mix of ambition, unique route, and amateur status really resonated with people, and not just the outdoorsy ones. Traffic poured in from Digg, Reddit and other link-sharing sites.Years later, I’m still feeling the reverberations of that trip. I’ve been back to the Wrangells once and have plans for another trip this year. I’m also packing today for a crazy Mexico adventure that I’ve been invited on because a couple of Alaska’s most-audacious wilderness travelers saw my photo essay and thought I’d be a good fit for their team. Looking back, it is comical how many doors have opened for me based on something that I never guessed would have that impact.

Forrest McCarthy midway through a 120 mile traverse of the Abaroka Beartooth Mountains. Photo by Jim Harris.

Future Direction.

There’s been this recent uptick in the ski industry’s acknowledgment that what we do is risky. At a fundamental level, action sports culture pushes the idea that “advancing the sport” or “pushing the envelope” is the loftiest goal an athlete can strive for. I think that presumption deserves some scrutiny because it is steering our risk-taking. We’re not going to revert to blue-square level skiing in movies but it’s worth acknowledging that there are perhaps less death-defying ways to “advance the sport.”For me, that means looking for trips that are challenging because they’re remote, or because they require an endurance component, or because they offer a quirky perspective on the norm. Both writers and photographers search for unique angles. As someone with a growing grasp of both, I’m positioned to connect interesting story ideas with smart photos.

Jim Harris’ Powder Magazine cover photo. Skier unknown.

Game Changers.

A few years ago, I watched an acquaintance trigger and then be swept by an avalanche. It was formative. It changed how I communicate with partners, how I plan for a tour, and is a continual reminder to make conservative choices.Soon after that accident, I began teaching avalanche classes. Now that I’ve shifted to proselytizing wilderness skiing for a living, teaching the prophylactic aspect of it feels essential. Not only does it feel like righteous work but teaching avy classes also helps keep my skills honed.At the other end of the spectrum, one of my photos is running on the cover of the new Powder Magazine Photo Annual. For someone who’s only been making a living as a photographer for just over a year, it’s like putting boots on at 9:30 and somehow still catching first chair. That cover isn’t recognition I’d expected to have so soon in my photo career, but I’m grateful for it.