The Objective:

As seen from afar:

Numbers that defined our world:

Wrangell St Elias NP and Preserve: 13,200,000 acres² (20,587 miles²)

Distance traveled: 430 miles (~220 miles on land and ~210 floating)

Time: 33 days (25 days on foot and 8 days paddling)

Distance on trail: 0

Resupplies: 3

Bears: 14

Other park visitors: 0

Jars Nutella eaten: 5

Gallons olive oil used: 0.7

Hours of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) performed: 1.2

Width of tent space space, per individual: 15”

Width of foam sleeping pads: 20”

On the long, unpaved road to McCarthy, with the bumpin’ sound system.

Almost midnight with a great bivy spot at the airstrip

When Chuck Norris goes to bed at night he checks underneath for Garry Green.

Cisco won the rock-paper-scissors for shotgun seating

Garry dropped us off at Tebay Lakes

As the sound of Garry’s plane faded, we found we were very, very far from anyone else.

At the end of the first day we could look down the Bremner valley and see the Copper River on the horizon. More than four weeks later we camped at the Bremner / Copper River confluence that’s just in front of the furthest mountains, almost a full circle.

Hauling the Great Grey Whale

The fireweed was going off in the smoky valleys.

Ready for the first of many balls-deep, glacially-fed river crossings.

Like this one, where we waited until morning to cross to avoid swimming.

This was the first time I’ve spent three days walking up a single valley.

Big, unnamed peaks every which way.

Cisco admiring the view from near camp

Over a pass…

And then onto a grizzly bear trail

In places, the bears don’t have a normal path. Generation after generation steps in the footprints of the last bear, carving long trains of divots in the tundra.

Shaking the reindeer lichen out of the VE-25.

After the first few days of 80 degrees and sunny, the weather shifted to cool and damp and is probably that way today too.

No photo-choppery. Serious.

Good thing I didn’t bring any down-filled gear.

Reluctant to get wet boots even wetter

Hiking through fireweed

Traversing down the Klu River valley. The easiest route was often to sidehill above the elevation where the vegetation turns to dense brush.

The view as the rain clouds cleared the next day

The maps cover four times the area of the 7.5-minute series I’m used to using. For a few days it felt like we were moving at a glacial pace until I adjusted to the scale.

I began noticing the first fall colors with the shift to cooler weather. This must’ve been around August 6th.

The first glacier crossing was only a mile or two long and rarely crevassed. Compared to the miles of wet scree and talus moraines we crossed that day, walking on the ice was cake.

To minimize the chance of bear encounters, our sleeping tent, kitchen, and food storage were spread far apart. Yellow tent on the right, blue and white speck of a kitchen Mid above the reflection line on the lake.

Not a big truck. Just a series of tubes.

We arrived to our first resupply site two days early. The Park maintains the bunkhouse from a small mine that operated for a few years in the 1930s and employs a volunteer to look after it in the summer.

Shortly after we arrived, a pair of Park Rangers flew in on a mission to aversively condition the local grizzle bears. Joe noticed one nearby and the commotion that ensued was spectacular.

In addition to good shots, they proved to be fine scrabble players too.

We spent down time exploring the area

And cutting unnecessary doo-dads off packs, you know, like zipper pulls.

Finally we got re-upped with more food. Garry settin’er down at the far end.

Refueled, we were on our way again.

On August 10 snow line wasn’t too far above camp.

Tundra walking

Rocky hopscotch for a few miles

The easy walking turned to willow and alder thrashing. Like all the way out the valley to the glacier.

Not so bad for bush-pushing, really.

Sand skiing down the moraine

Walking onto a lobe of a huge AK glacier

The water was so clear it was hard to gauge depth. Joe plays “Is it deeper than my pole?” “Yes, it is deeper than my pole.” Whatever the depth, it was delicious.

We did a lot of dunk ‘n drink without filtering the H2O. On lower 48 trips I nearly always treat water but here it just felt less imperative.

A cool looking cloud tunnel and a view of where we came from.

Up and over another group of peaks.

Big views everywhere

Then down the other side

Rain on Lupines.

Beautiful, bear scat covered camping

There was this great moment, one of those times I wish I would have taken a photo, where we stopped to admire some enormous prints in wet and spongy mud. After looking for a moment, Joe stepped forward and shifted his weight onto the mud next to the giant bear track. We saw his Vibram print, only half as deep as the bears, as he stepped away. Then, slowly, magically, the mud sponged back, refilling his step. Only the giant bear print remained. We blinked at each other and walked on.

Luckily the bears were preoccupied, as the berries were going off.

It’s amazing how one ingredient will improve plain, cold grapenuts and powdered milk.

We sometimes stretched our self-imposed “packs-on” waterbreaks by lounging without actually taking off packs. Whatever. The views were worth savoring.

Walking over a fertile, glacial-silt floodplain.

Each year a lake forms here, dammed by the glacier. Office building-sized ice chunks bob around in Iceberg Lake until, sometime mid-summer, the dam gives, sending a flood ripping down hundreds of miles of river.

The icebergs are stranded high and dry after Iceberg Lake drains.

Croc’ing across one of the tributaries that fill the lake each spring.

The Tana glacier is largely protected by a giant moat, but we found a spot to access it here, above the cave.

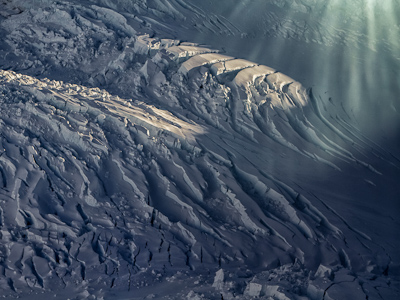

Tana Glacier from the air. The backcountry rangers and local guides were skeptical that there was a passable route across, and from the air, I would have agreed. We budgeted several days to cross it, but ended up making it in one long, 13 mile labyrinth push.

With an awesome vantage to choose the least-crevassed route, we nervously schemed the night before.

Then the next day we were off, blessed with decent visibility after a rainy night.

We stayed unroped, for the sake of speed, which was a reasonable decision below the firn line.

Another giant moulin hole, where the surface water plunges hundreds of feet into the inky depths of the glacier. It was so tempting to want to see inside, like a fly perched on the edge of a Venus Fly Trap.

We crossed over ridge, after ridge, after ridge, of rock-covered moraine

…Crampons off, crampons on, crampons off…

…Crampons back on. Places like this felt oddly similar to canyoneering here in Utah.

We found a moulin water refill after a long waterless section wandering through crevasses.

And finally onto dry land at the far edge of the glacier.

Between rain showers, we got just a bit of perspective of what we’d crossed

The next day we followed the banks of Granite Creek. Adam noted that if a “creek” is named on an AK map, it’s probably too big to cross without a Pack Raft. Indeed.

The “creek” is bigger than a many “rivers” in the lower 48. If you look closely you can see we’re a ways above it here.

A few moments of sun was all the excuse needed to explode packs in an effort to dry wet everything.

Nature imitates Andy Goldsworthy

I tended to not take the camera out of its dry box when it was raining, which was often. Here’s a rare picture of a long day of over-the-head alder shwacking.

And another from a different long day of thrashing.

Above brush line again, thankfully.

I got hit in the knee by a gallon milkjug-size chunk of ice while croc’ing across. It’s safe to say I’d never been hit by an iceberg before.

Garry coming in for the 2nd resupply on day 17

Out of the resupply gates, we were off and walking again

The last third of the hike had never been done. In fact, it sounds like our party might be the first to cross the Granite Range.

Fresh snow on the peaks in the background while crossing another ten miles of glacier.

It only looks roomy.

Pinned down by fog and rain, we practiced crevasse rescue systems to pass the time.

And all of 33 degrees too.

Looking through the window across another large, possibly uncrossed, and unnamed glacier.

We walked across plenty of “no fall zone” catwalks with dark voids to either side

Meandering through another heavily crevassed section, though it’s hard to tell from the photo.

If only we’d brought an innertube we could have had all kinds of first descents.

Though this would probably be the exit of a tube ride.

Chugach Bouldering Guide, pg 2245: These beautiful erratics are easily accessible with a short flight, several days glacier travel and a river crossing. Bring your brushes.

Down Goat Creek

The leaves quickly began yellowing as the nights grew colder.

A little fire and a hand-rolled tobacco on the banks of the Goat

Trundling opportunities abound. Helmets advisable.

Day 23 was misty and navigation was tricky until the clouds broke enough to allow a view 3500’ down into the Chitina River valley.

The following morning the river was socked in, but the peaks on the north of the Chitina were visible. Twaharpies Ridge in the center then University Peak on the right. University Peak is 12,000 above the river. Mt Bona, behind it in the clouds has 14,000’ of rise.

Enjoying the sun before our last day of hiking, we were slow to make it out of camp.

Fall in the alpine

Rather than bother with 5th-class grass downclimbing, Adam pioneered the technique of reaching out to grab a tree top then fire-poling down. Here Cisco perfects the technique.

Drying rack. Badum-ching!

The mushrooms were going off. Anyone know what type these are?

Amanitas in the ferns.

Day 25, the final resupply. Garry brought the raft but landed a mile and a half from the point he’d earlier picked out as the LZ, In a hurry, he dumped our gear, and flew off even as we hustled across river braids to reach him. We were left with packs, boots, axes, crampons, ropes, helmets, garbage, Rubbermaid bins and all sorts of crap we didn’t want to have squeeze into a little 14 foot raft.

The overloaded boat was christened with box wine.

And onward, to the ocean.

We stopped for a night at an old trappers cabin, maintained with help from locals. It was our first time being inside a building in weeks.

On the river I wore more layers that I’ve ever had on at one time before in my life. I felt like that kid in his snowsuit in Christmas Story. Something like 6 layers on top, and 3 more under the yellow Helly pants.

Sand camping. Eating, sleeping, tooth-brushing – everything is a little crunchier.

Rainy days on the river were borderline miserable.

Dry is much nicer

At the confluence with the Copper River we pulled out and walked to the town of Chitina, where there is one gas pump, one restaurant, and one bar. It was a little culture-shocking anyway.

After dinner we adjourned to the bar and soon after heard a thump as man fell off his barstool. He wasn’t just drunk. He was having a heart attack and so we began performing CPR. A short while later a local with EMT training and an AED defibrillator arrived. The patient didn’t come back, though not due to lack of effort on our part. The ambulance dispatched from 70 miles away was a long time coming. Celebration was cut short with the somber turn of events. “When I said we should close down the bar tonight, that’s not what I meant,” Joe remarked as we walked back to the raft that night.

The next day we wandered back to town and visited the EMT from the night before at his home. He had a fantastic vegetable garden, racks of salmon curing inside, and a winter’s worth of food stacked on deep shelves. After a few hours of Alaskan hospitality he sent us off with garbage sack stuffed with veggies.

Wild berries drying above the wood stove.

After weeks of dried foods, this is awesome

Hanging out in the garden was enormously uplifting to the morbid mood that lingered on from the night before.

We headed back to the river with an armful of salad a fresh outlook.

And on we floated.

The bar owner in Chitina had given us each a beer after the ambulance pulled away the previous night. This picture is a reminder to me of the helplessness as the barkeep had watched us, and wanting to contribute to the situation in some way, kept trying to hand us Pepsis and beers while we compressed and jaw-thrusted away. He finally succeeded by sending us off with a handfull of Buds. Back on the river, we toasted the patient. To Al Greise!

Camping so close to water is frowned upon followers of Leave No Trace principles. Though all four of us had spent years teaching the LNT guidelines, we often found sites like this to be the only places brush-free enough to set up a tent. On the other hand, I don’t think many others will camp in this exact spot.

Even with limited good camp sites, we still cooked away from the tents

Canned wild salmon + extra sharp cheddar + crackers = delicious

This fish wheel, a salmon catching device, had gone rogue and floated 70 or 80 miles down from Chitina.

Flying the Blue Peter nautical flag. Flown from a sailing ship, the flag means “this vessel is about to proceed sea” and is also a favorite emblem at Outward Bound, where the four of us teach mountaineering courses together.

We got a care package in our final resupply, mailed by friends and co-workers at Outward Bound. Thanks Emily.

Devil’s Club is covered with needle-like thorns, not just on the stems but on the leaves too. It is pretty though…

Bear patrol.

Most Alaskans will tell you that you’re nuts for traveling unarmed. I never felt threatened by bears, humans or otherwise, but blowing up small iceburgs from the raft was a checkmark on the bucket list.

Blam.

Yerba maté on a cold afternoon.

We camped just up from the Million Dollar Bridge

Childs Glacier was calving every few minutes. At our campsite not even a mile upstream, we listened to the rolling, thunderous sounds of ice breaking into the river all night

Brown bear waves from the bank

And suddenly we were at the Copper River Highway, where the river fans out and joins the ocean. Without much fanfare we rinsed, deflated, and rolled the raft, then started trying to hitch a ride into Cordova. There wasn’t a lot of traffic, but every vehicle was a large truck (often equipped with a little moose-lifting crane) who’s driver was out on a hunt. Every single moose hunter rolled down the window to ask if we were okay, then when we said we were, offered a ride when they made their way home. A few hours later a moose-sized man decided he’d had enough for the day and we loaded up our sandy pile of gear and squeezed in his pickup.

Cordova

Down by the docks

In true dirtbag style, we poached camping at the wharf

Before taking the fast ferry to Whittier the next morning.

We spent a few days in Seward couch surfing, eating expensive produce, and doing laundry.

And found enough work to pay for the drive back to Utah.

It was fall in the Chugach when we pointed the truck south.

Seward to Girdwood to Glenallen to the Yukon to British Columbia and the Cassiar to Smithers to Jasper to the Icefields Parkway to Highway 93 through Montucky to Highway 15 to SLC

The End.